“Metal Paintings” at Almine Rech, London, will be on view from September 12 — November 05, 2016

Opening on Monday, September 12th, 2016 from 6 – 8 pm

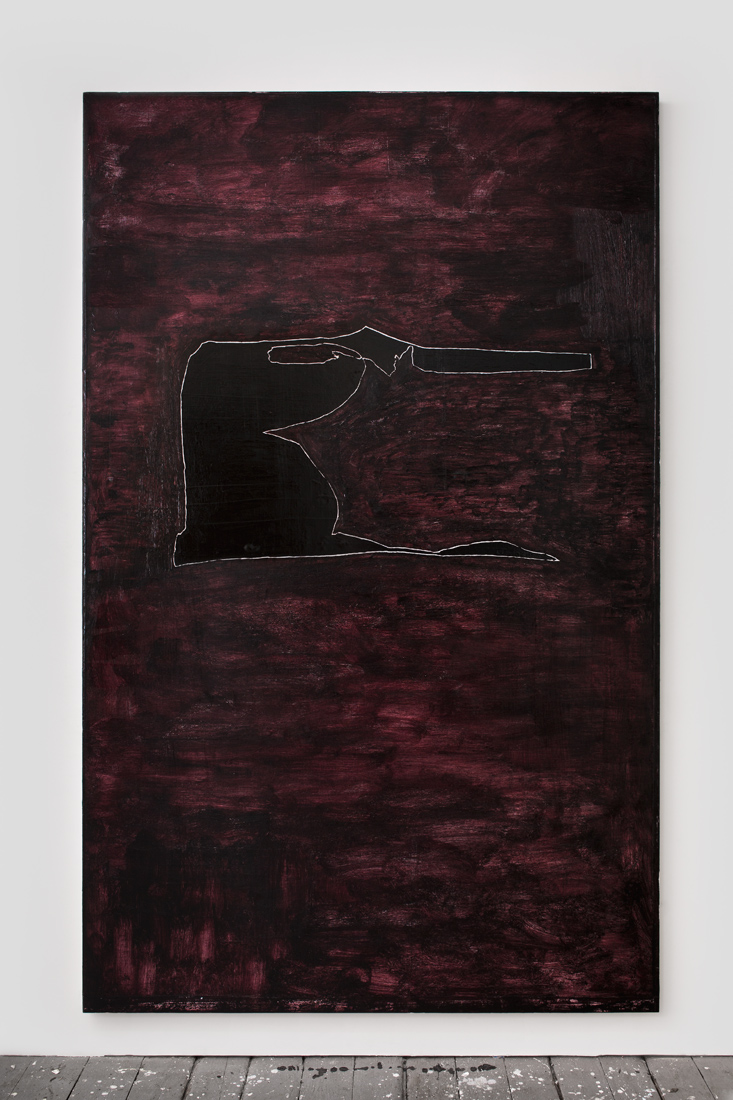

In Erik Lindman’s new works, the artist creates fresh abstract forms with a fine attunement to painterly details, constellated around various found surfaces and their treatment as compositional elements, surfaces, and supports. The majority of these new works are on primed or linen-wrapped panel that are affixed with thin sheets of aluminum or steel sheetmetal (or occasionally other flat, less-identifiable building materials), which are disguised and revealed to varying degrees by the application of paint on and around them. Colors and forms tend to accrete in the center of the painting, framed by white or unpainted space.

These found elements, which were picked up on regular walks by Lindman around the neighborhood of his studio in Harlem, Manhattan, are handled in a way that is characteristic of the artist’s cogitative approach, wherein material economy becomes an entry point to a particular type of seeing. To the extent that these compositions restrict form, color, and representation, they may elicit a subtle awareness through the shifts in perception that occur as a viewer’s focus wanders between the process of painting and its effects.

In his use of metal, Lindman attaches the found element to the support invisibly, then builds up paint around its edges, bringing it nearly level with the surrounding layers of paint so that it appears practically embedded in the painting’s surface. Almost flush with the ground of the paintings, these metal sectors receive paint in uneven ways and emit a faint, irrepressible sheen. The complicated flatness of each composition becomes a stage to exhibit detailed wrinkles, scratches, and striations in the paint, margins where color and metal meet, and expanses of thin pigment stretched across scuffed reflective veneers. Scrutinizing this paint on metal, we might add the layer of our own optical, tactile, and spatial experience. The vertical shape and human height of the pieces, along with their recurring narrow central figures, offer an analog to the instinctive, somatic self lying deep in our bodies. Awareness is a feedback loop created somewhere between our faculties and the object, while the boundaries of a painting could provide a theoretical if not a literal kind of mirror.

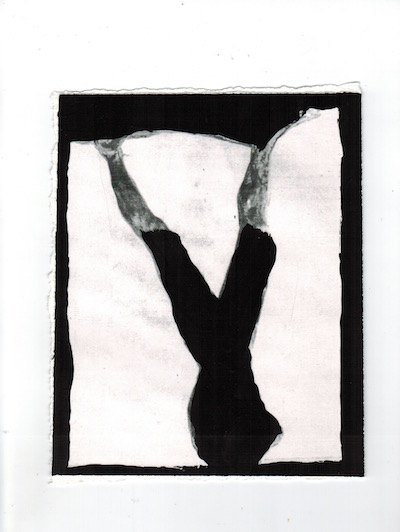

Lindman has also created several small works using fragments of steel welded to steel panels, occasionally adding oil paint. In these pieces, rather than inserting metal into a painting, the artist effectively creates the painting in metal; a stainless, enduring stand-in. But their modest scale diminishes any lingering bravado associated with their rugged materials and provides a counterpoint to the larger works on panel. Presence, an ambiguous noun attributable to both humans and objects, could also be the invisible stratum differentiating a painting from an image. Lindman creates frameworks for examining this liminal terrain through a sensitive range of micro-variegations. Transmitting exchanges between light shining forth from alloy, absorbed into painted color or blank primer, these works imagine an encounter with the irreducible.

Image: Untitled (Blue Bells), 2015-2016 Found surfaces (sheetmetal) and oil on linen over panel. 78 x 46 inches.